By Spencer Isitt, Salvage Crew Lead

It isn’t uncommon to find an old fluorescent light fixture hung from the trusses of Bellingham’s countless 20th-century-built garages and sheds. While it may seem great that they’re operating well past their designed life span, and their signature hum and green glow are certainly not without their charm, some older fluorescent lights may pose a potential health and environmental hazard when they’re decommissioned.

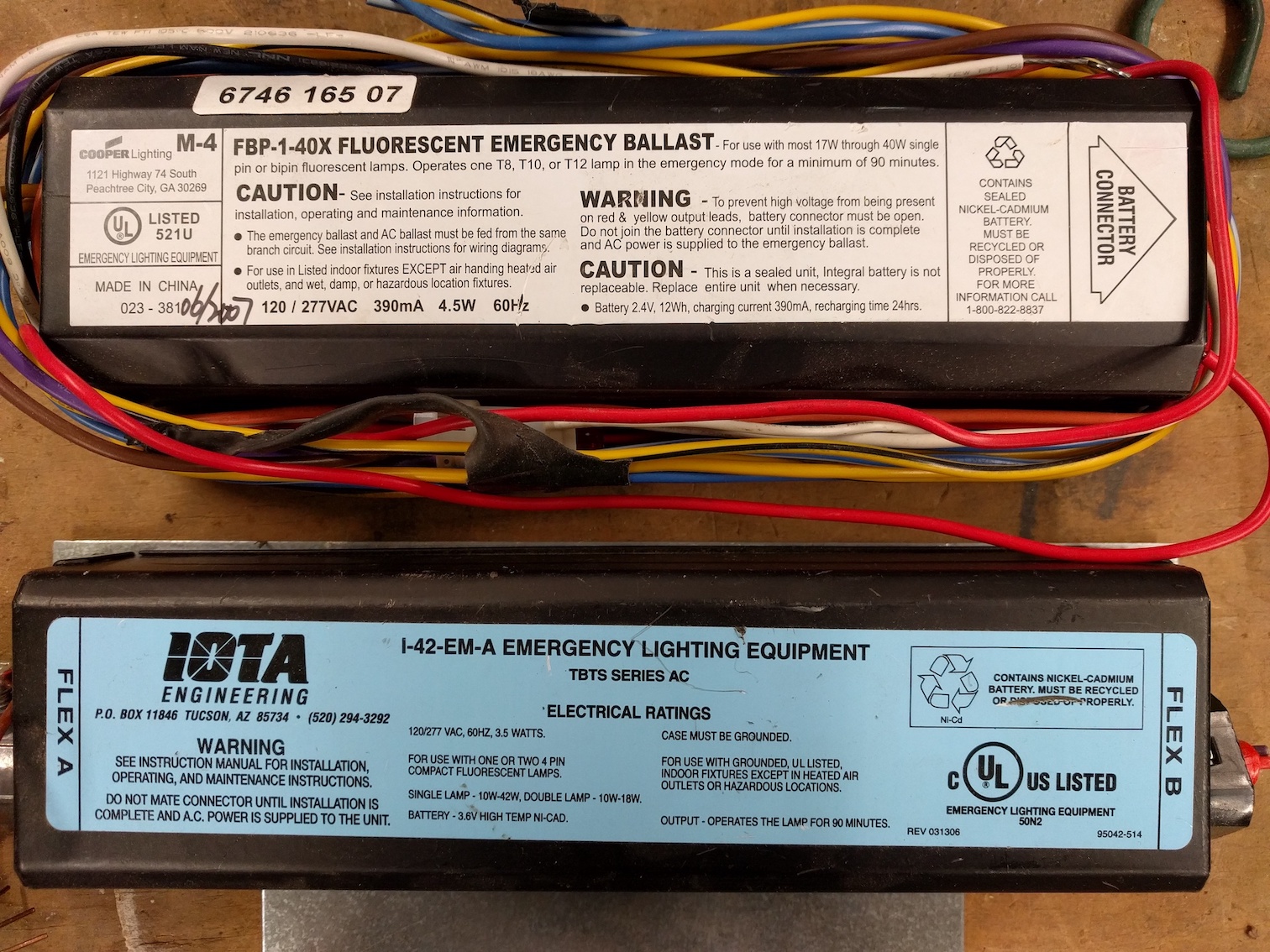

The mercury-containing fluorescent bulbs can be recycled at one of the many mercury-containing light bulb collection sites but the ballasts, which serve to regulate the electrical current in a fluorescent lighting system, may contain another substance of concern: PCBs.

PCBs (or Polychlorinated Biphenyls) are a group of man-made organic chemicals. They vary in consistency from thin, light-colored liquids to yellow or black waxy solids. Due to their non-flammability, chemical stability, high boiling point, and electrical insulating properties, PCBs were used in hundreds of industrial and commercial applications. These harmful chemicals are often found within the capacitors of fluorescent light ballasts manufactured prior to 1978.

PCBs easily make their way into our bodies, through skin contact, and as small particles in the water and food we eat and as dust in the air we breathe. PCBs have been demonstrated to cause a variety of adverse health effects. They are carcinogenic and are also related to a number of serious non-cancer health effects in humans and animals including: effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system, and endocrine system.

PCBs do not readily break down in the environment. They can remain for long periods of time, cycling between air, water, and soil, and can be carried far from where they were released into the environment. As a consequence, they are found all over the world. PCBs can accumulate in the leaves and above-ground parts of plants and food crops, as well as the bodies of small organisms and fish. As a result, people who ingest fish may be exposed to PCBs that have bio accumulated in the fish they are ingesting.

Prior to 1978, ballasts were magnetic. Starting in 1978, the EPA began requiring new electronic ballasts to be PCB free and for manufacturers to label new ballasts as “non PCB” “no PCB” or “PCB free”. However, this labelling system was expired in 1989. Today, we can check to see if a ballast contains PCB’s in four ways:

- If manufactured through 1979 and not labeled “No PCBs” assume it contains PCBs.

- If manufactured through 1979 and labeled “No PCBs” assume it is non-PCB.

- If manufactured after 1979 and through 1989, it should be labeled “No PCBs” and may be assumed to be non-PCB.

- If manufactured after 1989 it should be non-PCB but may not be labeled “No PCBs”.

While a damaged or leaking pre 1978 ballast is of the most concern, an intact unit may still emit small amounts of PCBs, though this amount is considered negligible by some. (OSHA, for example, has an air contaminant standard for exposure to PCB of up to 1 milligram of PCB per cubic meter of air averaged over an eight-hour work shift.)

If you have an intact PCB-containing ballast you would like to properly dispose of, the EPA recommends this simple procedure: “Wear rubber gloves that will not absorb PCB and consider using goggles or a face shield and a rubber apron. Avoid personal contamination by not touching your face while wearing gloves. Turn off the light fixture at the switch, and disconnect electricity at the fuse or breaker box. Let the ballast cool for 20 to 30 minutes before trying to remove the ballasts. Remove the metal cover over the wiring and ballast unit. Loosen the ballast by taking out the metal screws that hold it to the end of the fixture. Cut the electrical wires going to the ballast and remove the ballast.” You can then take it to the local Disposal of Toxics facility for proper disposal. If however, you find that the ballast is leaking fluid, special handling of the entire light fixture may be required. Contact your local Disposal of Toxics facility for more information.

For more information, visit the EPA’s website.